Shared solutions, stronger communities: Social economy and social innovation in Europe and Japan InsightsEssays: Civil Society in Japan

Posted on June 02, 2025

Shared solutions, stronger communities: Social economy and social innovation in Europe and Japan

Introduction

Social innovation offers solutions to major challenges such as aging populations, labour shortages, and social exclusion. By introducing new ideas, processes, or systems, it aims to improve people’s lives and strengthen communities. Practical examples include addressing healthcare gaps in remote areas, delivering community-driven educational programmes, and combating unemployment through multi-stakeholder collaboration.

In the European Union (EU), social innovation is largely supported by the European Social Fund (ESF). The ESF’s current 2021–2027 programming period has a budget of EUR 142.7 billion, providing targeted support for vulnerable individuals in areas such as education, employment, social welfare and social inclusion. While each member state also implements its own social policies using national budgets, the ESF provides EU-level funding. These two levels of support often complement each other, with ESF funds typically co-financing or enhancing national programmes to allow for a broader reach. By pooling resources into a dedicated institutional funding mechanism, the EU encourages organisations across its Member States to establish socially innovative, community-driven solutions to issues such as service provision gaps, unemployment, disability, etc.

A critical enabler of social innovation is the social economy, which comprises various entities such as associations, co-operatives, non-profit organisations, mutual societies and organisations, foundations and social enterprises. Their activities often prioritise societal objectives, values of solidarity, and democratic and participative governance over profit maximisation (OECD, 2022[1]).

Europe’s approach may offer valuable insights for Japan, where the notions of the social economy and social innovation are nascent but increasingly gaining momentum. This can be seen with the rise of social enterprises (known in Japan as impact startups) and the expansion of Japan’s co-operative movement, highlighted by the groundbreaking 2020 law on workers’ co-operatives. Against this background, this article takes a comparative look at Japan and Europe, focusing on societal challenges and the role played by the social economy in tackling them. Given that Japan’s non-profit sector heavily relies on private donations, membership fees and corporate philanthropy, the article also discusses how government support could enhance the sector’s visibility and accelerate further growth to address the country’s societal issues.

I currently work at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as a policy analyst for the Local Employment and Economic Development (LEED) Programme within the Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Cities and Regions. My research spans a range of topics, including the social economy, social innovation, social entrepreneurship, local development, and volunteering. Having been born in Tokyo but raised in various European cities, and having completed my graduate studies in Geneva, I aim to present an inter-regional perspective grounded in both European and Japanese contexts throughout this article.

Through my work at the OECD and background, I have had the opportunity to observe that European countries generally benefit from well-established institutional frameworks and strong policy support for the social economy, while Japan is navigating a very dynamic phase of experimentation and development in this field. This presents both challenges and opportunities for Japan, highlighting perhaps the need for public support and recognition of the social economy, while also acknowledging the rich potential for social innovation that arises in local communities.

Europe and Japan face working-age population decline, resulting in labour shortages

Europe’s working-age population is declining, resulting in labour shortages, with estimates revealing that the labour force will shrink by 15 million by 2040, and a further 27 million by 2050. Disparities also remain a major problem in the region, with over 20% of the European population (95 million) at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Amid issues such as climate change, a shrinking working-age population, and a widening inequality gap, a fair and inclusive growth model is needed (European Commission, n.d.[2]).

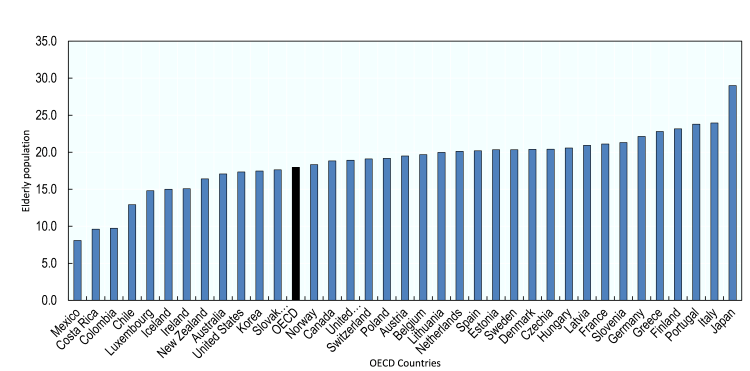

Japan has been facing similar obstacles. They have the largest percentage of elderly people among OECD countries (refer to Figure 1), making ageing a defining demographic challenge for the country. Combined with falling birth rates, Japan continues to navigate labour shortages and its shrinking workforce. Furthermore, equal access to opportunities is also a concern, considering that the nation’s gender pay gap is the fourth highest (21.3%) among all OECD countries (OECD, 2024[3]). As such, Japan could draw valuable insights from approaches pursued in Europe to address these challenges, including through the European Social Fund (ESF).

Figure 1. Elderly population across OECD Countries

Percentage of the population 65 years and above across OECD countries, 2022

Source: (OECD, n.d.[4])

In the EU, the European Social Fund supports projects that address labour shortages and ageing populations

Established in 1957, the ESF is among the EU’s most important funding instruments for investing in the core principles of the European Pillar for Social Rights: employment, education and skills, and social inclusion. The financing supports EU Member States to reduce unemployment, integrate disadvantaged and marginalised communities into society, and provide fairer life opportunities for all. As one of the two European Structural and Investment Funds, the ESF operates under seven-year periods and is the most important EU instrument in the field of labour policy.

Since the 2021–2027 programming period, the fund has operated under the new name ESF+, reflecting its expanded scope following the integration of several previously separate EU funding instruments. As part of the EU’s general budget—financed by annual contributions from Member States—ESF+ currently has a budget of EUR 142.7 billion. Given the fund’s purpose and the need for targeted support for the most vulnerable, the beneficiary groups include the unemployed or inactive, women, youth, elderly, ethnic minorities or migrants, and the disabled.

When it was first introduced in 1957, the ESF focused on labour mobility and vocational training to facilitate economic integration. It expanded during the 1980s and 1990s to include combating unemployment, enhancing social cohesion, and addressing regional disparities across Europe. At the turn of the 21st century, the ESF aligned more closely with the EU’s renewed strategic goals under the Lisbon Strategy, which emphasised inclusive growth and innovation, with funding priorities shifting towards skills development, lifelong learning, and social integration.

The ESF also supports social innovation as a driver of change

More recently, amid new challenges such as demographic change, digitalisation and globalisation, the ESF has placed an increased emphasis on social innovation. The ESF plays a crucial role in supporting vulnerable groups by promoting through social innovation solutions seeking to address issues ranging from unemployment to social discrimination. The ESF+ introduces a new requirement mandating that all Member States designate at least one priority area for social innovation, with strong financial incentives by permitting countries to claim 95% of EU co-financing for socially innovative projects. These changes reflect a shift towards more innovative strategies aimed at tackling societal challenges and fostering inclusive growth.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was the first inter-governmental organisation to define social innovation in 2000: “Creating and implementing new solutions that entail conceptual, process, product, or organisational changes, with the ultimate goal of enhancing the welfare and well-being of individuals and communities”. In other words, social innovation involves creating news ideas or systems that improves the lives of individuals and communities.

Social innovation is often driven by the social economy, which is formed by a diverse range of actors including non-profit organisations (NPOs), cooperatives, mutual benefit societies, associations, foundations, charities and social enterprises. Their activities are primarily driven by societal objectives, values of solidarity, and democratic and participative governance over profit maximisation (OECD, 2022[1]).

An upcoming OECD report looks into the enabling conditions for social innovation and numerous approaches in starting, scaling and sustaining it. The report builds on national evaluations of 96 ESF-funded initiatives during the 2014-2020 programming period, stakeholder consultations, interviews with key stakeholders and experts in the field, and extensive research. The report will provide valuable lessons and insights on how the European Social Fund (ESF) has contributed to addressing social issues. It will focus on innovative forms of collaboration among multiple stakeholders and across different policy areas. Additionally, the report will highlight best practice cases across EU Member States in areas such as education, labour market integration, and social inclusion for underserved groups, including women, migrants, and younger generations. These evidence-based findings and policy recommendations will inform future programming cycles of the ESF.

Lessons for Japan from the social economy and social innovation

As Japan is looking for ways to address labour shortages, promote active ageing, and respond to demographic change, the growing social economy and social innovation present timely opportunities. One opportunity is to strengthen institutional support for social economy entities and other social innovation initiatives. For instance, NPOs grew from 10 000 nationwide in the early 2000s to almost 50 000 today, while social enterprises (also known as impact startups in Japan) have increased ten-fold in just three years, reaching 206 (Impact Startup Association, 2025[5]). The co-operative movement is also substantial in Japan, with 65 million members and an annual turnover of USD 145 billion (ICA-AP, 2019[6]). This was further strengthened by the 2020 Workers Co-operative Act which encourages senior citizens’ employment and provides opportunities for women and youth in remote areas.

Various social economy entities actively tackle labour shortages and provide labour integration opportunities for women. An example of a social economy entity is Mama Square, an impact startup that was inspired by the desire of mothers who wish to work while also spending time with their children. Mama Square offers a working space which is equipped with a kids’ space – separated by glass windows – to allow mothers to work with a peace of mind. Since its establishment in 2014, they have signed cooperation agreements with dozens of cities across Japan to implement the initiative, even receiving the EY Innovative Startup Award for Child Rearing in 2018. These forms of innovative solutions to tackle social disparities is of particular importance in Japan, where 31% of women do not seek employment due to childbirth and childcare challenges, despite wanting to work. This underscores the necessity to secure an environment that allows women to continue working after pregnancy and childbirth (Nakamura et al., 2022[7]).

Another example is the Ueda Workers’ Cooperative, which was formed in 2023 shortly after the adoption of the Workers Co-operative Act. According to the representative director, Takao Kitazawa, this workers’ co-operative model enabled him to pursue meaningful work after his retirement, as it allows the workers themselves to take lead and be the driving force in their work. Comprised of 13 senior workers, the Ueda Workers’ Co-operative conducts home equipment renovation, gardening, maintenance and cleanups for the elderly, highlighting that mutual support among senior citizens is the key to addressing demographic challenges in Japan. With falling birth rates and rapid ageing, this co-operative provides a sustainable solution to seniors who wish to remain active and continue working.

Conclusion

Japan might wish to consider opportunities to establish an institutionalised funding scheme like the ESF to harness its growing social economy. Given that the country grapples with many similar problems as Europe, the region’s approach of leveraging the social economy through ESF may provide valuable insights. In doing so, Japan may be interested in the OECD Toolkit for the Social Economy (available in English and Japanese), which is an instrument for policy makers and social economy actors to better implement the nine building blocks of the OECD Recommendation on the Social and Solidarity Economy and Social Innovation. Such long-term financial support would encourage the experimentation of innovative solutions, helping to unlock the full potential of Japan’s growing social economy to address pressing societal challenges.

――――

You can also read the Japanese translation here.

――――

About the author:

Moe Shiojiri is a policy analyst for the Local Employment and Economic Development (LEED) Programme at the OECD’s Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Cities and Regions. Her work focuses on the social economy, social innovation, local development, and volunteering. She holds a master’s in international and development studies from the Geneva Graduate Institute and a bachelor’s in political science from Sophia University. Moe has a strong passion for policy and development, shaped by her experience working across NGOs, international organisations, and embassies. She was born in Tokyo but raised in Budapest, Brussels and London, bringing a global perspective to her work.

References

| European Commission (n.d.), What is the ESF+?, https://european-social-fund-plus.ec.europa.eu/en/what-esf. |

[2] |

| ICA-AP (2019), Cooperatives in Japan, https://icaap.coop/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/2019-Japan-country-snapshot.pdf. |

[6] |

| Impact Startup Association (2025), Members, https://impact-startup.or.jp/en. |

[5] |

| Nakamura, Y. et al. (2022), “Occupational stress is associated with job performance among pregnant women in Japan: comparison with similar age group of women”, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, Vol. 22/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05082-3. |

[7] |

| OECD (2024), OECD Employment Outlook 2024 – Country Notes: Japan, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2024/06/oecd-employment-outlook-2024-country-notes_6910072b/japan_85e15368.html. |

[3] |

| OECD (2022), Recommendation on Social and Solidarity Economy and Social Innovation, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0472. |

[1] |

| OECD (n.d.), OECD Data Explorer, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/?lc=en. |

[4] |

Recent Articles

- Our vision for the future of private NPO support centers

- “Neither isolated, nor alone”: Insights from the frontlines of women’s end-of-life support

- Changing society from within a 15-minute walk

- How are NPO support centers balancing staff protection and abusive behavior?: Strategies for managing customer harassment

- A view on realignment in U.S. private philanthropy

- Adapting global goals to local action: The SAVE JAPAN Project approach