Looking at Peace Education and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons from Hiroshima: Current Situations and the Challenges We Face in Japan InsightsEssays: Civil Society in JapanVoices from JNPOCOther Topics

Posted on March 12, 2021

In 2018, Japan NPO Center (JNPOC) started a news & commentary site called “NPO CROSS” to discuss the role of NPOs/NGOs and civil society as well as social issues in Japan and abroad. We post articles contributed by various stakeholders, including NPOs, foundations, corporations, and volunteer writers.

For this JNPOC’s English site, we select some translated articles from NPO CROSS to introduce to our English-speaking readers.

Looking at Peace Education and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons from Hiroshima

Current Situations and the Challenges We Face in Japan

The article was covered and written by Yuki Moriyama, a volunteer writer of the Information Dissemination Volunteer Project by Japan NPO Center. Original article in Japanese

August 6, 1945 at 8:15 in the morning. That was when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. When Hiroshima natives move out to other parts of Japan, they are sometimes shocked to find that this date and time do not ring a bell with other Japanese people. In fact, I was one of those Hiroshima natives in shock myself. Having an overwhelming majority of people around me not recognize this date and time, or realizing people are not even interested, was unthinkable to me when I lived in Hiroshima. Since I left my hometown, as each year goes by, I feel more and more strongly that fewer and fewer people really get this significance of August 6th.

This year was the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. 2020 has also become a memorable year because it was confirmed that the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will enter into force. However, many people in Japan most likely feel that all of this exists far away from their own lives, as if it is some distant event completely unrelated to them. Even in this kind of social climate, there are people in Hiroshima today who have been engaged in peace activism for decades. Wanting to dig deeper into the discomfort I have been feeling since I moved away from Hiroshima, I interviewed one such person, Ms. Tomoko Watanabe, who is the board director of a nonprofit organization called ANT-Hiroshima.

ANT is a Hiroshima-based NGO involved in international cooperation, peace education, and peacebuilding efforts. ANT’s goal is to work together with countries around the world and realize what they refer to as greater peace through utilizing the memories, experiences, and testimonies of the people of Hiroshima as a city that experienced the atomic bomb.

What We Don’t Know about the Hibakusha

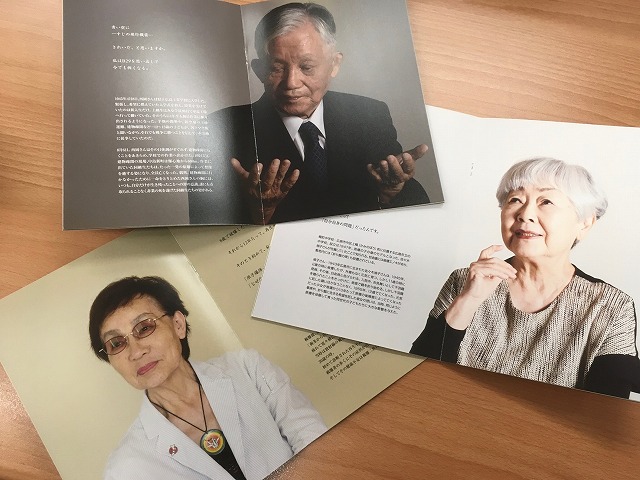

Photo Caption: ANT-Hiroshima is creating a booklet series called “Hiroshima: A Face.” ANT-Hiroshima records and disseminates the testimonies of individual hibakushas.

How much do you know about the hibakusha, the people who survived the atomic bomb?

Originally, peace education in Japan began with teachers who experienced the atomic bombing firsthand. Nowadays, however, the people who teach often do not know the realities of the atomic bombings. For this reason, ANT’s peace education includes stories about the realities of the atomic bombings that are not covered in the school curriculum. For example, they talk about the four categories of hibakusha, the Japanese word for the atomic bomb survivors. The term hibakusha typically conjures up a strong image of people who were directly exposed to the atomic bomb, but survivorship actually encompasses all of the following categories of people.

1. People who were directly exposed to the atomic bomb

2. People who arrived within about 2-kilometer radius of the hypocenter within 2 weeks after the bombing

3. People who provided first aid to those injured by the atomic bomb and treated the remains of those killed by it

4. People who were exposed to the atomic bomb as fetuses in utero and people who were exposed to the so-called “black rain” that fell immediately after the bombing also suffer from the same aftereffects as the other types of hibakushas

“Hibakushas who have courageously broken the silence after many years and begun to talk about their experiences of the atomic bombing are determined not to let anyone else experience the same suffering as they did,” says Ms. Watanabe, who is in touch with the hibakushas often. She emphasizes, “That is their one true motivation in sharing their testimonies.”

At ANT, they sometimes ask the hibakushas to team up with young people in their work. “When I work with the hibakushas, I treat them as individual persons. They are not ‘the hibakusha’ to us but ‘Mr. or Ms. So-and-So.’ We believe that we can only truly inherit and pass on the experiences of the atomic bombing within these interpersonal relationships among people.”

Features of ANT-Hiroshima’s Peace Education

One of the unique features of ANT’s peace education activities is that university student interns serve as speakers. The objective is to have younger students in primary and secondary schools, who are listening to their stories, relate better to the content coming from speakers closer in age, as if older siblings are sharing stories with their younger siblings.

The materials used in their peace education activities are also selected on a case-by-case basis, based on the audience’s ages and backgrounds such as the region of Japan where the activity takes place or the nationalities of people in attendance. For example, ANT may use the picture-story show “Chisai Ari to Okina Ki (Little Ant and the Big Tree)” about a tree that was exposed to the atomic bomb, the picture book “Orizuru no Tabi (The Journey of a Paper Crane),” a series of hibakusha testimony videos, pictures drawn by hibakushas, and poems by children who died from the atomic bomb.

Comparing Peace Education in Japan and Germany

When it comes to the damages caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese military covered up the truth until the war ended on August 15, 1945. In the following ten years, the United States, who occupied Japan, imposed restrictions on the disclosure of information as well. This period is referred to as “The Lost Decade” in Hiroshima. Because truths about such significant damage was hidden for so many years, people around the world, including those in Japan, do not know what happened under the mushroom cloud.

Thanks to the activities of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, people around the world are finally becoming aware of the threat of nuclear weapons. However, in Japan, the reality of war and the atomic bombings is still not taught in depth in schools.

A German university student intern at ANT told me that in Germany, not only do they teach about the systemic massacre of Jews or about camps like Auschwitz in schools, but they also emphasize visiting the sites and learning about the history of the war firsthand. The intern was surprised to learn that in Japan, war and the atomic bombing are not taught in detail in schools. In addition, while public funding for organizations engaged in peace education is quite substantial in Germany, it is almost nonexistent in Japan. I must conclude that there is difference between the two countries when it comes to the enthusiasm towards and institutionalized support for peace education efforts.

Views on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

On January 22, 2021, Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will finally enter into force. Ms. Watanabe reports, “The hibakusha and those of us who have been working on peace activism have been longing for this day, so we are shedding tears of joy.” On the other hand, the truth is that TPNW is not well known in Japan, and, in fact, it is not well known even among Hiroshima citizens.

TPNW prohibits the development, possession, and use of nuclear weapons on the grounds that their use violates international laws applicable in the event of armed conflict. It was adopted in July 2017 with 122 states in the United Nations voting in favor. The treaty’s entry into force was confirmed after it met the requirement of ratification by 50 states.

However, TPNW has not been ratified by the U.S. and Russia that possess 90% of the world’s nuclear weapons, China and other nuclear powers, or allies of nuclear-armed states such as Japan which depends on America’s nuclear deterrence. Even though Japan is the only country to have experienced a nuclear war, it is not participating in this treaty. “Japan’s role is to ratify the treaty and then urge the nuclear-armed states to work toward nuclear disarmament,” Ms. Watanabe appeals.

As for what we the citizens can do, Ms. Watanabe says, “We should continue to think about what kind of country Japan wants to be in the future and lobby the Japanese government.” Recently, people have become more proactive in their social actions, and the change is noticeable among young people such as university students. Organizations have launched among them. For example, the “Go To HIJUN! Campaign” ultimately aims for Japan’s ratification of TPNW, and they ask Diet members for their stance on nuclear policy and publicize the responses. “Kakuwaka Hiroshima,” which is short for Hiroshima Young Voters’ Group to Learn about Nuclear Policy, has also launched their activities. It is vital that each of us think for ourselves and take action toward nuclear abolition, steadily and persistently, no matter how slow that effort may seem.

In Closing

——————–

Original text by Yuki MORIYAMA, posted in NPO CROSS on December 21, 2020: translated by JNPOC

Recent Articles

- Shared solutions, stronger communities: Social economy and social innovation in Europe and Japan

- NPO support for disaster victims: Key discussion points

- Beyond support: Fostering genuine dialogues

- Reconsidering the significance of public comments

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice