Supporting the Poor to Become More Independent JCN Report

Posted on October 01, 2015

Post-disaster outbreak of poverty

In the pre-disaster era, the term of “poverty” had mainly been used in Japan within the context of providing support for homeless people in urban areas. On 3.11, however, hundreds of thousands of people in the disaster-affected areas of Tohoku lost their homes, household effects, cars, public transportation, jobs, friends, families, and communities in an instant, and found themselves suddenly confronted by poverty. These people have received assistance through a support system for the victims as well as through Japan’s livelihood protection system.

Many of the victims were given emergency assistance, such as donations and rent subsidies for temporary housing, and on the surface, there seemed to be a sharp drop in the number of people on welfare. An increasing trend has been observed since 2012, however, due to the decline in support systems related to the disaster.

Over three and a half years have passed since the earthquake, and as people transition from life in temporary housing facilities to more permanent dwellings (e.g. public housing for disaster recovery), new problems are emerging, such as the burden of paying rent, loneliness and isolation, moving difficulties, families being broken up, and the need to find a guarantor to move into a new place. Many of the people who are rebuilding on their own are also struggling with long-term financial burdens such as capital investment and loan repayments.

The region as a whole is facing a number of problems that may create a hotbed for poverty, including a lack of people able to manage the communities, labor shortages, loss of employment opportunities, and moving difficulties related to depopulation and a rapidly aging society.

Enforcing the Support for the Independence of Poor Persons Act

Japan’s economic slump and widening economic disparities grew critical after the Lehman Shock in 2008. The current ratio of people in non-regular employment (i.e. unstable jobs) has surpassed 35% of the overall workforce. More than 2 million people are receiving welfare assistance (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare).

Japan’s social security system has until now been supported by a First Safety Net that includes pension and employment insurance for those in stable employment, and a Third Safety Net that includes public assistance mostly for people unable to work for reasons such as illness and disability.

With the worsening economic conditions and changes in the employment structure (e.g. expansion of the temporary work sector), however, it is believed that the people caught in between the First and Third Safety Nets– that is, those who are in an unstable situation (economic, family, housing, physical and mental) despite having jobs– are rapidly growing in number, leading to a sudden increase in the number of people receiving welfare payments.

From April 2015, a new system under the Support for the Independence of Poor Persons Act was introduced nationwide to help people who are unable to work for various reasons. Positioned as a Second Safety Net, the law is expected to be of major assistance to those affected by the disaster, in addition to the various victim support systems already being provided by authorities such as the Reconstruction Agency.

Future Issues

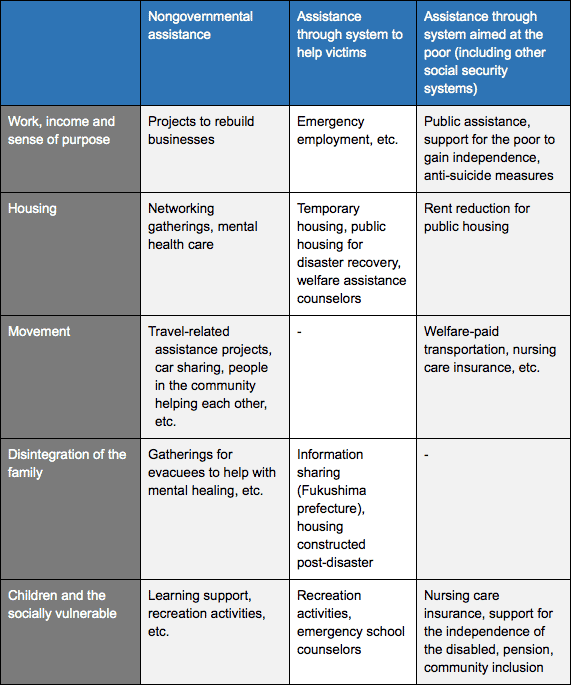

It is believed that support to counter poverty will be needed in the areas outlined below.

1. Employment difficulties (economic poverty and lack of sense of purpose)

Many people have lost their jobs for reasons that include their workplace being washed away by the tsunami. Loss of income not only leads to poverty, but also affects people psychologically (e.g. sense of purpose, confidence). There are also a number of reasons why a person might have difficulty finding employment – it is not necessarily only because of the disaster.

Intermediate employment through agricultural programs

Intermediate employment through agricultural programs

2. Housing difficulties (need for housing)

Many problems can be hard to identify on the surface, such as the constraints of long-term living in temporary housing facilities, leases that cannot be concluded due to the lack of a guarantor, the economic burden of rent and loan payments, and, in the case of people working on disaster-related projects, instability in employment and housing (i.e. dormitory life), after which they are laid off and become homeless and sleep in internet cafes, their cars, or on the streets.

3. Moving difficulties (restrictions in ability to move around)

Much of the public transportation network on the coastal areas, such as roads and railways, has been destroyed, and many people have lost their means of transportation. The resulting restrictions on their ability to move around have left them unable to go to the hospital, do their shopping, and engage with the community, and has increased their economic burden. For the elderly and disabled, the impact of this often spills over to result in poverty for the family as a whole.

Providing a mobility-impaired temporary housing resident with transportation services

Providing a mobility-impaired temporary housing resident with transportation services

4. Disintegration of the family (loss of human relations)

Short-term and irreversible family disintegration due to loss of home in the affected areas has progressed, threatening the quality of life and sense of purpose of the people affected. Throughout Japan, and not just in Tohoku, the problems of depopulation and aging are becoming more and more critical, but in Fukushima in particular, the impact of the harm caused by radiation has driven many multi-generational households apart.

Study tour participants visiting the house of a woman who returned to her hometown, leaving her son and grandchildren in another town. (Kawauchi-mura, Fukushima)

Study tour participants visiting the house of a woman who returned to her hometown, leaving her son and grandchildren in another town. (Kawauchi-mura, Fukushima)

5. Poverty among children and the socially vulnerable (chain reaction of poverty)

Many children have been unable to attend school due to factors such as psychological injuries from the disaster, or being in single-parent families that are struggling financially. Parks and school grounds have been leveled either by the disaster or in order to build housing, so children are unable to study, play, and interact with each other. Furthermore, long-term living in unstable conditions is causing more and more physical, psychological, and economic burdens on parents and children, in some cases leading to a state of poverty. There is also recognition of the need to assist those most easily affected by the disaster, such as non-Japanese people and the disabled.

The potential for poverty already existed in the area before the disaster. The fact is that several problems had already fallen through gaps in the system, and these quickly became critical as a result of the disaster.

This report was a part of JCN Report Vol.2 and originally published in January 2015. JCN Report has been created by JCN (Japan Civil Network of Disaster Relief in Japan) to spread the understanding the state of Tohoku today to support recovery efforts throughout country.

About JCN (Japan Civil Network of Disaster Relief in East Japan)

Recent Articles

- Shared solutions, stronger communities: Social economy and social innovation in Europe and Japan

- NPO support for disaster victims: Key discussion points

- Beyond support: Fostering genuine dialogues

- Reconsidering the significance of public comments

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice